Herbert Wehner

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Herbert Wehner" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Herbert Wehner | |

|---|---|

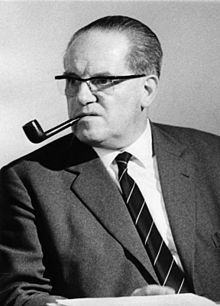

Iconic portrait of Minister Wehner with his pipe, 1966 | |

| Leader of the Opposition | |

| In office 1 October 1982 – 6 March 1983 | |

| Chancellor | Helmut Kohl |

| Preceded by | Helmut Kohl |

| Succeeded by | Hans-Jochen Vogel |

| Leader of the Social Democratic Party in the Bundestag | |

| In office 22 October 1969 – 8 March 1983 | |

| Leader | Willy Brandt |

| Preceded by | Helmut Schmidt |

| Succeeded by | Hans-Jochen Vogel |

| Federal Minister of Intra-German Relations | |

| In office 1 December 1966 – 21 October 1969 | |

| Chancellor | Kurt Georg Kiesinger |

| Preceded by | Johann Baptist Gradl |

| Succeeded by | Egon Franke |

| Member of the Bundestag for Hamburg-Harburg | |

| In office 14 August 1949 – 6 March 1983 | |

| Preceded by | Parliament established |

| Succeeded by | Hans-Ulrich Klose |

| Member of the Landtag of Saxony | |

| In office 10 July 1930 – 18 June 1931 | |

| Preceded by | Multi-member district |

| Succeeded by | Max Silbermann |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Herbert Richard Wehner (1906-07-11)11 July 1906 Dresden, Kingdom of Saxony, German Empire |

| Died | 19 January 1990(1990-01-19) (aged 83) Bonn, North Rhine-Westphalia, West Germany |

| Political party | Communist Party (1927–1942) Social Democratic Party (1946–1990) |

| Spouse(s) |

Charlotte Burmester

(m. 1944; died 1979)Greta Burmester (m. 1983) |

| Children | 2 (adopted) |

| Occupation | Politician |

| Signature | |

Central institution membership

| |

Herbert Richard Wehner (11 July 1906 – 19 January 1990) was a German politician. A former member of the Communist Party, he joined the Social Democrats (SPD) after World War II. He served as Federal Minister of Intra-German Relations from 1966 to 1969 and thereafter as chairman of the SPD parliamentary group in the Bundestag until 1983.[1]

During his tenure in the Bundestag from 1949 to 1983, Wehner became (in-)famous for his caustic rhetoric and heckling style, often hurling personal insults at MPs with whom he disagreed. He holds the record for official censures (77 by one count, 78 or 79 by others) handed down by the presiding officer.

Life

[edit]Herbert Wehner was born in Dresden, the son of a shoemaker. His father was active in his trade union and a member of the Social Democratic Party. More radical than his father, Wehner engaged in anarcho-syndicalist circles around Erich Mühsam, driven by the 1923 invasion of Reichswehr troops into the Free State of Saxony at the behest of the DVP–SPD Reich government of Chancellor Gustav Stresemann. He also fell out with Mühsam, whose pacifist manners he rejected and was accused of stealing money by him, which Wehner never denied.[2] He finally joined the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) in 1927, becoming an official of the party's Rote Hilfe organisation the same year.

Wehner rose quickly and was elected to the Landtag state legislature of Saxony in 1930. Nevertheless, he resigned one year later to work at the KPD politburo in Berlin with Walter Ulbricht. After Hitler's seizure of power in January 1933, he participated in the communist resistance against the Nazi regime from the Saar Protectorate. When the Saar was re-incorporated in 1935, Wehner went into exile, first to Paris, then in 1937 to Moscow, where he lived at Hotel Lux, wrote for the Deutsche Zentral-Zeitung and had to face Joseph Stalin's Great Purge of 1937–38.[3] After Wehner's death, German news magazine Der Spiegel documented accusations that he informed the NKVD on several party fellows like Hugo Eberlein, presumably to save his own life.[4] After being sent to neutral Sweden in 1941 in order to re-enter Germany, he was arrested at Stockholm and interned for espionage in 1942. Whether he deliberately went into custody has not been conclusively established; at least he was excluded from the Communist Party by politburo chief Wilhelm Pieck.[5]

Upon his return to Germany in 1946, Wehner joined the Social Democratic Party in Hamburg and soon became an aide of Chairman Kurt Schumacher. After the 1949 federal election he entered the Bundestag parliament and remained an MP until his retirement from politics in 1983, from 1952 to 1958 also as a member of the European Parliament. In 1957/58 and again from 1964 to 1966, he served as deputy chairman of the SPD parliamentary group. Wehner was instrumental in the party's adoption of the Godesberg Program in which the Social Democrats repudiated a fixation on Marxist ideology and broadened its appeal.[6] In 1966, he was named Federal Minister for All-German Affairs in the CDU–SPD grand coalition government of Chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger.[7] The cooperation between the ex-communist and the former member of the Nazi Party went well; Wehner even promised the CDU partners to stabilize the coalition by backing the implementation of a plurality voting system, which he later denoted as "nonsense".

When the SPD assumed the reins of government under Chancellor Willy Brandt upon the 1969 federal election, Wehner became chairman of the SPD parliamentary faction. He was known as a hard disciplinarian who kept his members in line. When the CDU on 27 April 1972 waged a constructive vote of no confidence against Brandt, he ordered the SPD deputies not to participate in the ballot in order to exclude possible bribed dissidents. The opposing candidate Rainer Barzel failed to reach the absolute majority by two votes. After Brandt was re-elected in 1972, the relations between the two men cooled down during the 1973 oil crisis, when Wehner increasingly viewed the chancellor's policies as indecisive. In the course of the Guillaume Affair, he did not make great efforts to persuade Brandt to stay in office and promoted the chancellorship of Helmut Schmidt.[8]

Already Father of the House from 1980, Wehner did not seek re-election in 1983, after the social-liberal coalition had finally broken up. He retired to Bonn, where he died in 1990 at the age of 83 after a long illness, suffering from Diabetes mellitus and Binswanger's disease.

Rhetoric

[edit]Wehner held an infamous reputation among members of the Bundestag (and the public) for his sharp, and often insulting, rhetoric towards MPs that disagreed with him. His remarks about political opponents often revolved around insulting word plays with their respective last names. One notable exception is his pejorative neologism "Düffeldoffel" which he used to insult Helmut Kohl. His sharp comments would not stop at his own party either: When the SPD-MP Franz Josef Zebisch complained about how the alphabetic seating order in the Bundestag in the 1960s left him at the back of the room, Wehner told him to just rename himself to “Comrade Asshole”.

German media occasionally depicts Wehner and CSU-politician Franz Josef Strauß to have been political rivals as both had highly influential yet never the highest positions within their respective parties and Strauß was also known for a fierce albeit less personally insulting rhetoric.

Wehner's reception across the aisle among CDU/CSU politicians was mostly negative due to his rhetoric. However, CDU politician Heiner Geißler acknowledged Wehner's uncompromising style of standing up for his party's positions as "the biggest parliamentary howitzer of all time".

Further reading

[edit]- Bedürftig, Friedemann: Die Leiden des jungen Wehner: Dokumentiert in einer Brieffreundschaft in bewegter Zeit 1924–1926. Parthas, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-86601-059-1.

- Leugers-Scherzberg, August H.: Die Wandlung des Herbert Wehner. Von der Volksfront zur großen Koalition. Propyläen, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-549-07155-8.

- Meyer, Christoph: Herbert Wehner. Biographie. dtv, München 2006, ISBN 3-423-24551-4.

References

[edit]- ^ Hermann Weber; Andreas Herbst. "Wehner, Herbert". Handbuch der Deutschen Kommunisten. Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin & Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur, Berlin. Retrieved 28 November 2024.

- ^ Helga Döring: Kein Befehlen, kein Gehorchen! Bern 2011. p. 199 [in German]

- ^ „Emigranten: Hotel Lux“ Archived 12 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine Geo Epoche, No. 38 (August 2009). Retrieved 12 November 2011 (in German)

- ^ "Menschlicher Abschaum" Der Spiegel (31 December 1990). Retrieved 15 November 2011 (in German)

- ^ "Herbert Wehner". gdw-berlin.de. German Resistance Memorial Center. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

- ^ "SPD Politician Herbert Wehner (October 1954)". ghdi.ghi-dc.org. German History in Documents and Images. October 1954. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

- ^ "Herbert Wehner". Oxford Reference. Oxford University Press. 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

- ^ "Wehner, Herbert". willy-brandt-biography.com. Willy Brandt Biografie. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Academics | |

| Artists | |

| People | |

| Other | |

- 1906 births

- 1990 deaths

- Refugees from Nazi Germany in the Soviet Union

- Members of the Bundestag for Hamburg

- Members of the Bundestag 1980–1983

- Members of the Bundestag 1976–1980

- Members of the Bundestag 1972–1976

- Members of the Bundestag 1969–1972

- Members of the Bundestag 1965–1969

- Members of the Bundestag 1961–1965

- Members of the Bundestag 1957–1961

- Members of the Bundestag 1953–1957

- Members of the Bundestag 1949–1953

- German communists

- Members of the Politburo of the Communist Party of Germany

- Alterspräsidents of the Bundestag

- Grand Crosses 1st class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Members of the Bundestag for the Social Democratic Party of Germany

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with German-language sources (de)

- Articles with short description

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Use dmy dates from March 2021

- Articles needing additional references from November 2011

- All articles needing additional references

- Commons category link is on Wikidata